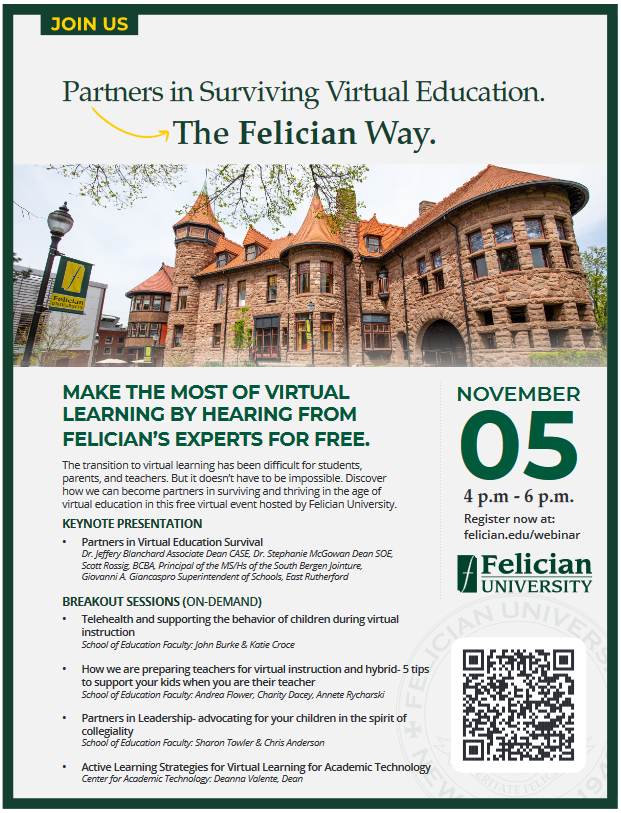

Partners in Surviving Virtual Education

- Felician Online

- November 5, 2020

- Thursday, 4:00PM to Thursday, 6:00PM

Contact event manager

Book your tickets

Partners in Surviving Virtual Education

Felician Online

Thursday, 4:00PM to Thursday, 6:00PM

November 5, 2020

000000

Partners in Surviving Virtual Education

MAKE THE MOST OF VIRTUAL LEARNING BY HEARING FROM FELICIAN’S EXPERTS FOR FREE.

The transition to virtual learning has been difficult for students, parents, and teachers. But it doesn’t have to be impossible. Discover how we can become partners in surviving and thriving in the age of virtual education in this free virtual event hosted by Felician University.

KEYNOTE PRESENTATION

- Partners in Virtual Education Survival

Dr. Jeffery Blanchard Associate Dean CASE; Dr. Stephanie McGowan, Dean SOE;

Scott Rossig, BCBA, Principal of the MS/Hs of the South Bergen Jointure;

Giovanni A. Giancaspro, Superintendent of Schools, East Rutherford

BREAKOUT SESSIONS (ON-DEMAND)

- Telehealth and Supporting the Behavior of Children During Virtual Instruction

School of Education Faculty: John Burke & Katie Croce

-

How We Are Preparing Teachers for Virtual Instruction and Hybrid- 5 Tips to Support Your Kids When You Are Their Teacher

School of Education Faculty: Andrea Flower, Charity Dacey, Annete Rycharski

- Partners in Leadership- Advocating for Your Children in the Spirit of Collegiality

School of Education Faculty: Sharon Towler & Chris Anderson

- Active Learning Strategies for Virtual Learning for Academic Technology

Center for Academic Technology: Deanna Valente, Dean

REGISTER TODAY